sir peter cook’s cities exhibition at richard saltoun gallery

Following last year’s expansive City Landscape exhibition at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark, Sir Peter Cook returns with a new, immersive show at Richard Saltoun Gallery in London to mark his six-decade-long career. Drawing on his work over the past 60 years, the upcoming Cities exhibition features a site-specific architectural environment and immersive Virtual Reality experience produced especially for the gallery, together with a selection of drawings and paintings that trace his radical vision. Visitors are invited to have a ‘visual discussion’ about cities: cities reimagined and dismembered and cities climbing over themselves to become new forms. ‘This exhibition is a continuous attempt to extend the vocabulary of my work,’ Cook tells designboom in a recent interview, which you can read in full below.

The exhibition, which runs from July 19 to September 16, 2023, also coincides with the 60th anniversary of the Living City show at the Insititute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), held at that time on the same street as the Richard Saltoun Gallery. In Living City, Peter Cook, together with Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Michael Webb – who later joined forces to found the celebrated neo-futurist group, Archigram – extolled the transience and serendipity of cities with hot images collaged into a three dimensional triangulated framework. Archigram brought forward radical ideas that have continued to inspire worldwide, including pioneers of high-tech architecture such as Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, and Rem Koolhaas.

All Wall (2023) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

all images courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery

a 60-year legacy of avant-garde & neo-futuristic drawings

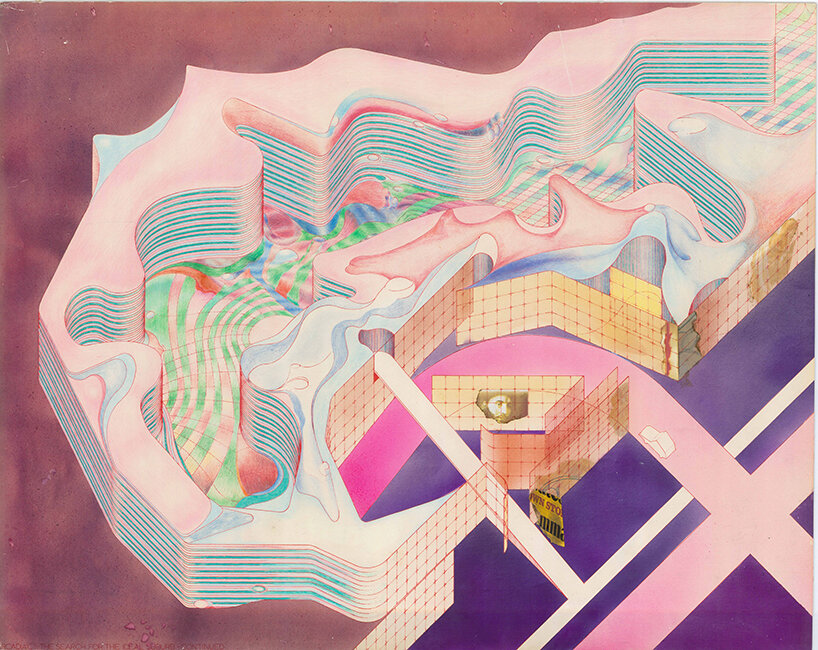

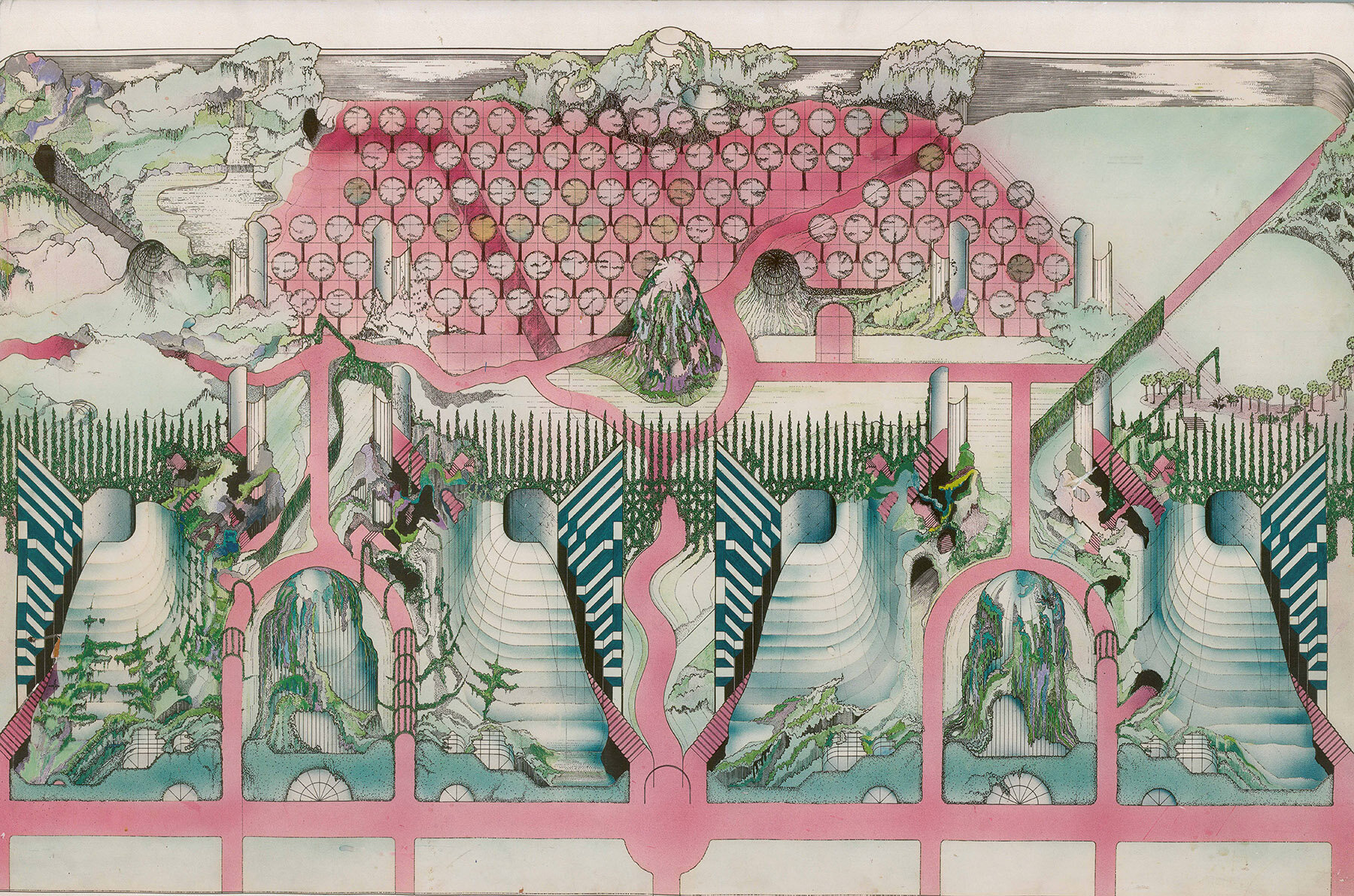

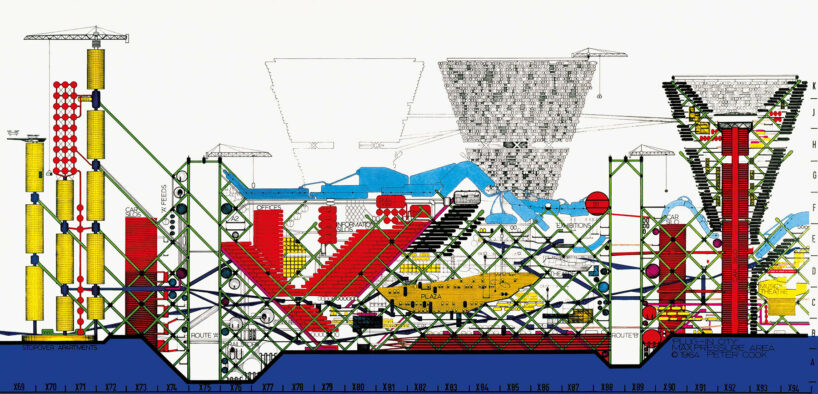

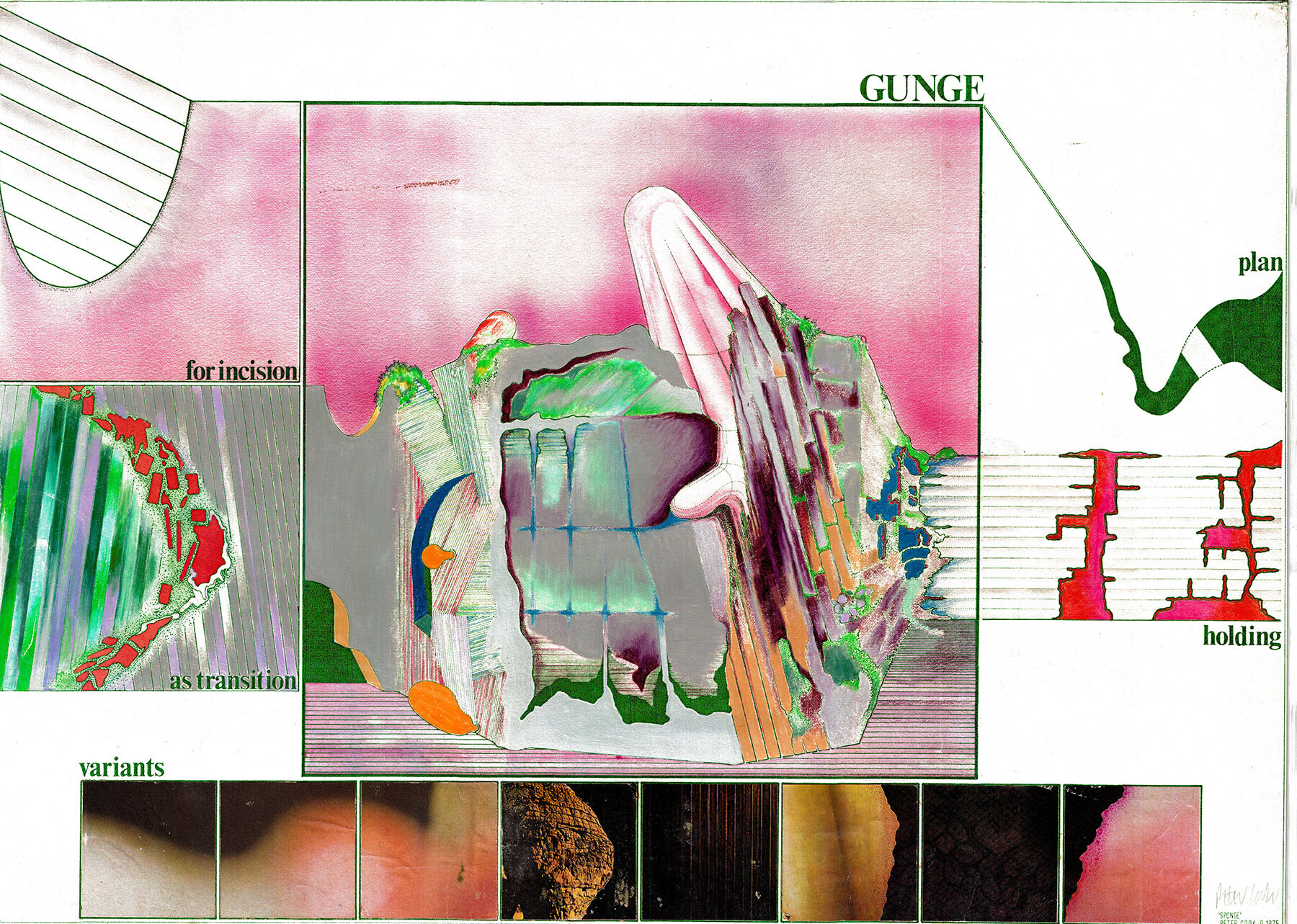

Since the 1960s, Peter Cook has maintained an interest in the theoretical field of architecture and examining the future through the medium of drawing. By lifting the limitations of the physical world, drawing has freed him from the constraints of sites and economics,reinventing the look and function of cities through a range of unique, innovative designs. This becomes apparent in his ongoing series of works titled Arcadia, which he has produced continuously throughout his career. This project explores alternative suburbian lifestyles inspired by his English town upbringing. Another notable project of his is the Plug-in City (also exhibited in ICA’s Living City). Developed between 1963 and 1966, these plans showed various iterations of prefabricated modular residences or ‘capsules’, modes of transportation, and other essential services that ‘plug in’ to one central hyper structure. In the 1970s these designs softened and started to involve layers and vegetation.

A tendency to mix and discover hybrids of natural conditions mixed with the mechanical and artificial accelerated through the 1980s and 1990s. Since then, the extension of the inherited architectural vocabulary has become a major preoccupation, exemplified by the artist’s series of ongoing architectural projects with the Cook Haffner Architecture Platform (CHAP). Read on as Sir Peter Cook describes and reflects on his upcoming Cities exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery, celebrating his ongoing pursuit of a new architectural vocabulary and imagery.

Sunshine Village (2021) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

interview with sir peter cook

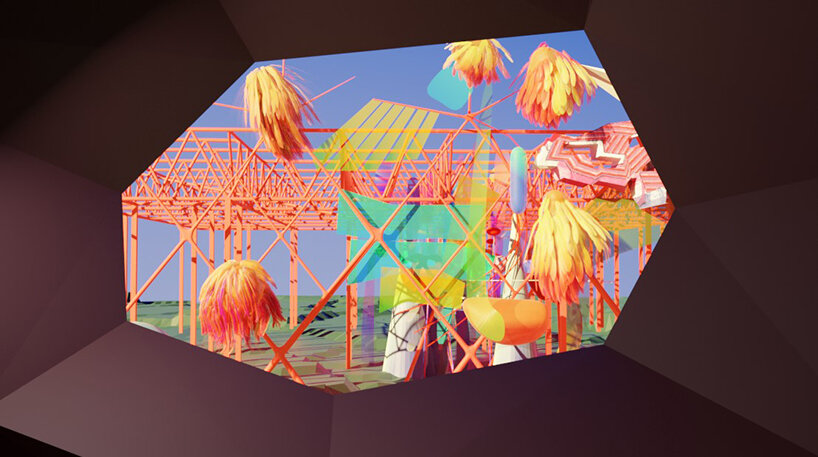

designboom (DB): Walk us through the spatial experience of your upcoming Cities exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery and how Virtual Reality will come into play.

Peter Cook (PC): The exhibition is in three rooms. And as you enter at a right angle from the main direction of the gallery, you will be confronted by a sort of full height and width of the room; you can’t actually walk right inside it, but it is something that almost embraces you. And it is derivative of one or two of my fairly recent drawings that explore what can be enclosed in a wall. In this instance, the wall is opened up and fragmented. This is a series of experiments we’re doing with some of my drawings in which the drawing is, to some extent, dismembered and then even integrated with dismembered versions of other drawings. This exhibition is a continuous attempt to extend the vocabulary of my work; I’m always trying to probe an extension of the architectural vocabulary. And I tried to turn this into another vocabulary, a pathway toward the making up of formal enclosures. So I’m trying to see if I’m able to produce things further in that direction until the actual enclosures become the drawing.

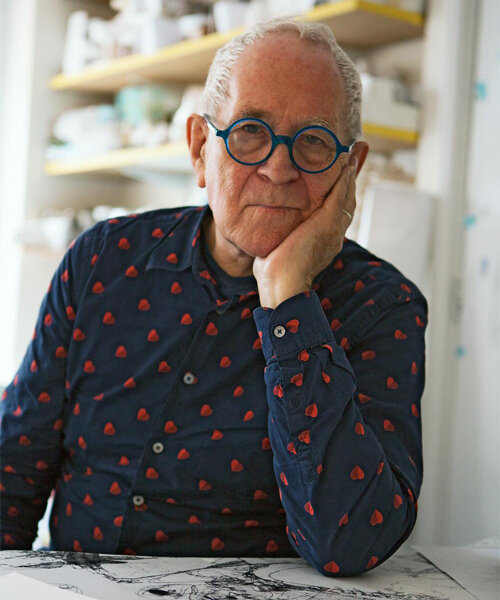

Sir Peter Cook talking with designboom from his London office | image © designboom

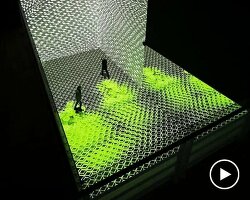

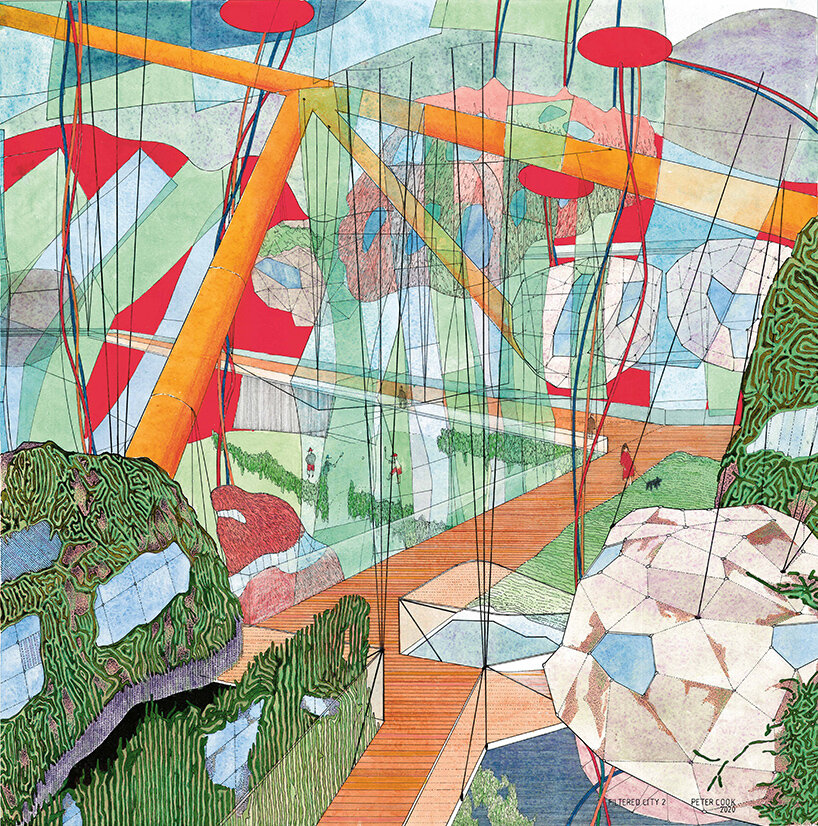

PC: Having engaged with that, we then turn to the main axis of the three galleries, where we have one of my most popular drawings, which has a virtual reality version of it; visitors can go ‘inside’ the drawing. So suddenly, the drawing, which was previously static, has some of its elements coming to life: they open up, they drift, then they move through the space. And then there are a series of drawings themselves spanning over quite a long period. We don’t show any large numbers of any particular period; we go back to the 70s and, in one case, through the 80s, the 90s, right up to earlier this year. They’re almost samples of different periods of my work, some involving kind of mysterious conditions such as dreaming up spacious spacelessness. Some look at substance, alternative types of material from which we might make architecture. Some are actually projects for cities. All of them involve an observation of city form, really.

The city has been my canvas for a long time. And in that respect, there’s quite an interesting historical condition because, God help us, sixty years ago, before Archigram was called Archigram, I did an exhibition (Living City) with a series of friends who most of them became part of Archigram; it was at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, when it still had its premises across the street from the Saltoun gallery, before moving to a grander place. Similarly to this current exhibition, it was a construction that you walked inside. And it used a lot of graphics. I think my own graphics at that time were still relatively underdeveloped. I think that what I was drawing at that time had the embryons of my Plug-In City and so on. They were still fairly crude; they were still drawn in black and white, not in color. I didn’t have, I suppose, the technique I later developed at my disposal.

Filter City (2020s) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

PC: And, of course, what I like to do is to constantly speculate. I have a drawing on the board right now that I’m doing, which is what I call Intrusive Landscape; it is the making of a kind of landscape and then showing all the different things that might pop out of the landscape, like tectonics coming out of it; that’s merely one thing that I returned to many times. And it will be interesting to see what correlation people can make between the large-scale drawings and the drawings in a frame. We are showing one or two quite large drawings; the gallery is not big enough to hold everything. I did have a huge exhibition at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark last year, which showed 120 items — large, smaller, etc.. This current exhibition will be showing probably about 20 items, something of that order. And I think it will be a kind of sampling, a little bit leaning towards the stuff I’ve done in the last three years, but not entirely, and also some casting back. I call it Cities because, in a way, all of the examples are fragments of cities — either reflecting upon known cities, or suggestions of parts of cities.

I can’t help thinking my next exhibition should be my next building. And I’m very interested in the relationship between the drawing and what it is suggesting should happen. I’m always interested in it being like a soft way of introducing a radical architecture. I’m still, instinctively, a radical architect. I’m using the art space condition, meaning the gallery, in the same way that I would use publications many times to propagate the extension of the vocabulary of architecture a propos the city. That’s really my mission: to extend the vocabulary of architecture.

Filter City (2020s) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: Speaking of your next building, which speculative city of yours would you like to see actualized?

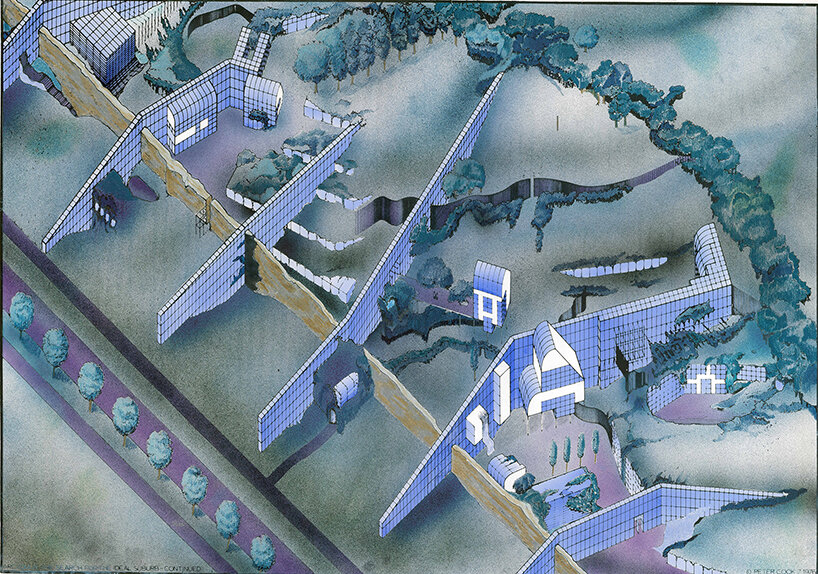

PC: Funnily enough, I used the term Arcadia twice; I used it in the 70s. And just a few weeks ago, I completed a drawing called ‘Another Arcadia’, which is an idealized Garden City. It’s this sort of place where vegetation, gadgets, robots, and enclosures all mix together to create a hybrid. That’s something that has interested me for a very long time. So I would love to make a Garden City, one of my own period. I lived in many English cities as a child, as a son of an army officer; my favorite condition is a medium-sized city, not giant cities, because they’re tough to comprehend. I mean, I love Tokyo and Los Angeles and so on, but they are very complicated to summarize, whereas a small city can project the atmosphere of a small city — and I think I could design one. I had a few attempts in the past, but nobody has done.

Arcadia ‘B’ – the search for an ‘ideal Suburbia’ – continued (1977-78) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on card, 59 x 83 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: You mentioned the meshing of gadgets and vegetation. With new technologies pervading the world today, and based on your Plug-in City model, how do you envision Artificial Intelligence and AR/VR being plugged into future cities?

PC: We are increasingly finding that there are smart devices built into fairly commonplace conditions. There are more and more bits and pieces of the known environment that respond and provide and don’t have to have all the cumbersome mechanics of human intervention. I’m one of many other architects that have been involved in Saudi Arabia’s NEOM City project. There, you have the proposition of a whole smart component where cars will not be necessary. One is thinking in three dimensions, and the three-dimensional city, I think, is a very interesting territory where you move diagonally through space. You may climb up quite high, and you don’t have to lay everything as a compass on the ground. But on the other hand, you don’t have to have just faceless slab blocks.

Arcadia ‘C’ – the search for an ‘ideal Suburbia’ – continued (1980s) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on card, 59 x 73 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: While essentially futuristic, your body of work could allude to ancient architectural systems, with many of their techniques being revisited today. What are your thoughts on embedding ancestral designs into cities of tomorrow?

PC: If my work does have a visual similarity to it, then I would slightly consider it a failure (laughs). I’m not a great lover of the antiques. When I was at school, I was quite good at history. I could write essays very easily. But I never really got interested till about the period of 1850 onwards, because that’s when the railways started to propagate. And I grew up knowing about railways; I know towns with railways, with gasworks, with trams, and trucks, and roads, and cranes. I’m not really interested in something that I feel I have no direct contact with. I was taken once to the Acropolis; I was giving a lecture in Athens, and a very important historian was to take me out there. While I was honored, I was also quite bored by it. I used to, as a child, on the other hand, insist on dragging my parents in England to see Roman remains as a phenomenon, and I used to go look at castles. I got out of that when I went to an architecture school at 16. I’d already read The Corbusier and was interested in modern architecture. I had to work on measured drawings of churches, tombs, neo-classical orders, etc. So I went backward. At 14, I was more of a modernist than I had to be at 17. You know, I don’t even like Victorian paintings or Victorian crafts, or old chairs.

My musical taste is a little bit backed on that, although I certainly veer more toward 20th century rather than 18th century music. I have a son who’s a music producer. He does very avant-garde music, and he’s more famous than me anyhow (laughs). I find some of his music a bit hard going; everybody has a limit. It could be argued whether I’m a 21st or 20th-century futurist; I would be willing to debate. If I take a really honest, intellectual position on it, I don’t go back beyond 1850 or 1900. That’s when it gets really interesting: the development of early airplanes, railways etc.. Really anything that I can see happening is interesting to me.

Arcadia ‘A’ (1977) | Print, 85 x 127 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: Could you elaborate on that last point? How has your drawing/creative process evolved over the years?

PC: I can answer that by discussing what I’ve been working on today. I had this notion of a landscape that can absorb many, many artifacts. And so I’ve set it up on paper, slightly in perspective — looking down on the landscape. I set it as a kind of grid in perspective. And then I drew, in pencil, some peaks, tops of hills, with different heights. Some of the peaks are placed toward the edge and not at the center of the patch. That’s just a grid that allows me to move around. I start working on the notion of a series of hills and found that it has a valley condition. So I work on it.

The high points are usually celebrated with some constructed object; it may be playing with the surface, it may be playing with something poking up. But these tops will be marked and celebrated, each one in its own way. Then comes the intensification of something, a drift — I’m very interesting in drifts. And then I play with the surfaces, some of them obviously mechanical, containing strange objects, or having things poking out. Just yesterday, I drew a square patch with a few sticks or poles hanging, alluding to an anticipation of something being done. The implication is that there is a construction or constructed condition that’s going to happen.

Filter City (2020s) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

PC: I’m also working on this notion of a high rise, like a castle, coming out of the forest. If we look at the UK, there is a need for expanded towns; this is a great demand for housing. There are many small towns in England inhabited by maybe 1,000 people, but then we sort of stick more people in these towns, creating a really dreary piece of suburbia. So I thought: why not grab the bull by the horns and put them all in the high rise and then put the high rise in the forest. Two places I often visit are Tel Aviv and Frankfurt; both are characterized by small towns with high rises surrounding them.

I did a drawing a couple of years ago on the subject; I’m now incorporating a piece of that into this landscape. One of the hills has high-rises coming out of the forest. And when we take the forest away, it’s a kind of statement; you suddenly reveal the hill below the forest. Ultimately, I’m using forests as one of the pieces of my vocabulary. I’m using rocks as another piece. I’m using what you do in a cutting, in a crevasse, as part of my vocabulary. I’m using what you do on the top of things as part of my vocabulary. I’m sort of recreating, in a way, a language of urbanization, except it’s not very urban.

Discreet City (2022) | ink, color, pencil, watercolor on paper | © Peter Cook

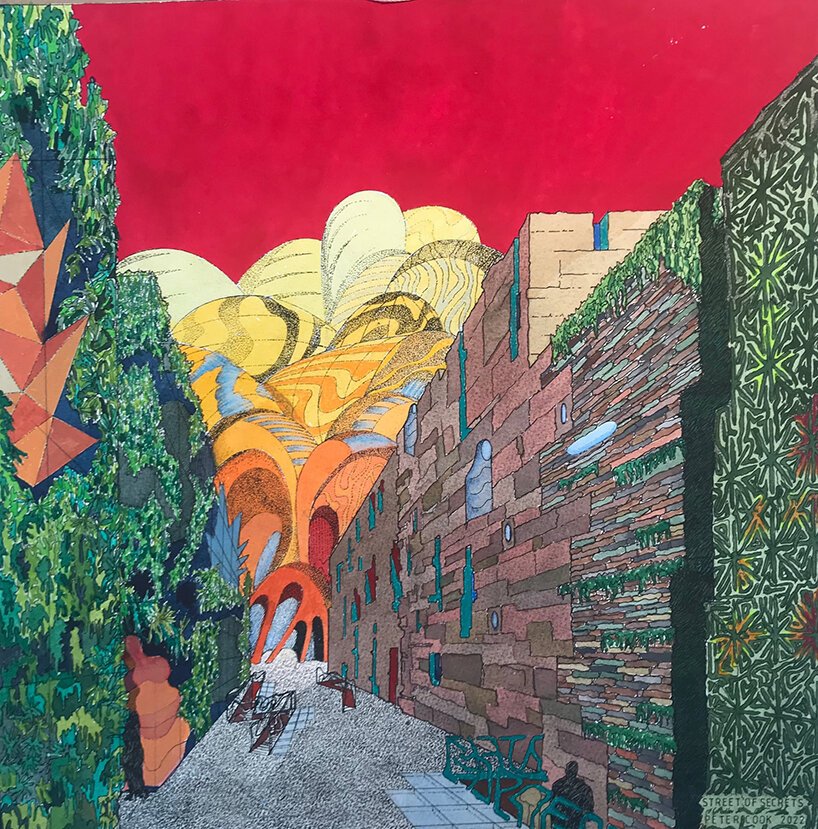

PC: Some drawings are more concentrated, like the one I did recently, called ‘All Wall’. The wall is quite complex, but it is a wall. This recent landscape drawing is rolling on; several conversations will be held together, and this means the objects drawn are fairly small scale. That’s because I’m trying to experiment with different things seen in juxtaposition. But I’m not entirely sure how the landscape will evolve. I have a vague idea; I will invent the program as I go along and say: ‘There could be too many trees here. Let’s reduce the trees; let’s make more of a valley; let’s look at crops, crevices, tops, patterns.‘ It’s like somebody who plays the piano, putting together a piece, which shows their dexterity in chord making, in fast finger movement, in counterpoint here, in tonality there. You do the exercises involved in a number of different demonstrations. Sometimes, though, the drawing takes over. It sort of tells you what it wants to be. And you drop that in the program. You just let it go.

Filter Cities (2023) | VR | © Peter Cook

DB: Speaking of ‘All Wall’, this drawing depicts a wall surface containing chambers. It’s an interesting combination of systems of communications, vegetation, and open zones. What other architectural elements do you wish to explore further in your work?

PC: There’s another drawing that I’m working on at home, which looks at corners. I’m very interested in corners, at when a surface turns. I think the Victorians were better at corners than we are. Modernists weren’t great at that. You know, modernism wanted consistency and cleanness, and then if you had to go around the corner, it sort of stopped then went around. The Victorians, and particularly northern Europe, were very good at that. If you go to Stockholm or Oslo, a bit toward Germany, they always mark a corner and make it look special. They celebrate the corner. It has a certain power that pops out first, and then you get the main body of the building. So in this new drawing, I contrive three corners. Again, I don’t really know how this will come together in the end; I have a vague idea, still.

Plug-in City (1970/2012) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on board, 79 x 164 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: How do you decide on the composition of your color palettes? Is there a particular emotion or impression that you wish to convey through your unique chromatic mix?

PC: My wife is also an architect and probably my best critic. She says that sometimes I lose the plot on the color and that my drawings looked better before they were colored. The coloring is sometimes a bit of a whim. Alongside the City exhibition, I also have six drawings hung up on a wall around the corner from the Royal Academy, which you can buy as prints. They’re some of my most popular works; it’s always surprising to find out which drawings become best sellers. It’s never the ones you think.

As for one of the popular ones this year, I still don’t quite like the coloring, but 13 people have already bought prints, maybe 20 by now — so somebody likes that color! It may have to do with other things going on in that drawing; I use a lot of airbrush on that one, and it’s sort of folding over. Bits of it will be recreated at the Saltoun Gallery as a big piece. But I’m a little bit surprised that the color, which I wouldn’t have used if I had to draw the piece again, seems to be popular. Richard Saltoun said himself that people don’t buy very much green, but I noticed that one my best sellers has a lot of green in it; it is a nice drawing, the prettiest one, almost too pretty. You know, after a while of completing a drawing, I can look back and say:’ That’s a bit gutsy, that’s a bit pretty, that’s a bit gloomy, that’s a bit provocative, that’s a bit problematic.’

Street of Secrets (2022) | ink, color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 50 cm | © Peter Cook

DB: While your work touches upon many themes, what do you think should be of primary concern for architects when building future urban spaces?

PC: We can go back to my theme; the extension of the vocabulary. I think worldwide, there are about five or six sets of vocabularies. We have what we call here the new London vernacular, but you see the same thing in Germany or America. The steady, rectangular windows — the beige, gray buildings. Not really modernist nor revivalist — more like non-committal. Terrible stuff. Then you get people looking at traditional materials: sticks, wood, bamboo, and weaving them together. Then you get those Zaha Hadid-like, computer-generated surfaces, weaving, folding, based on artificial materials, concrete, and composites. In the north, you still get an amount of stick and panel architecture. And then, if you go to the Middle East, you have the typical stone and concrete systems, which, to be fair are sometimes made and built quite stylishly, but they’re still limited to stone and concrete. It seems like most people are afraid to venture outside a certain way of doing; they want to keep it very safe. But I think there’s much more architecture out there that people can explore. Sadly, many can’t be bothered or are apprehensive. They don’t want to take the risk; they don’t think the material will work; they say it’s too expensive. If you make windows in funny shapes, they’re always more expensive. But really, this is about architects being scared to try something new.

That’s why I like to go to Japan. Japanese are very good at combining all sorts of different things; they have a natural design sense. They enjoy play. As soon as you get to China, for example, it gets stiffer. In America, while some architects are really interesting, the majority are very careful and safe and predictable. They have amazing manufucaturing capabilities but they tend to stay very squared, including architecture students. It’s a terrible generalization, but that is my observation as a teacher. But there are places in the world where amazing things are happening, like Chile, Portugal, and Australia. So personally, I’m intrigued by eccentricity and projects that touch upon the eccentric — only as clues for what might be extensions of the vocabulary.

Gunge (1977) | color pencil, watercolor on paper, 50 x 70 cm | © Peter Cook

project info:

exhibition name: Cities

architect and interviewee: Sir Peter Cook | @sirpetercookatchap

location: Richard Saltoun Gallery | @richardsaltoungallery, London

running dates: July 19 – September 16, 2023

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (259)

EXHIBITION DESIGN (501)

PETER COOK (4)

VIRTUAL AND AUGMENTED REALITY (189)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.